BNF 以及 EBNF

- Part.1.A 为什么一定要掌握自学能力?

- Part.1.B 为什么把编程当作自学的入口?

- Part.1.C 只靠阅读习得新技能

- Part.1.D 开始阅读前的一些准备

- Part.1.E.1 入口

- Part.1.E.2 值及其相应的运算

- Part.1.E.3 流程控制

- Part.1.E.4 函数

- Part.1.E.5 字符串

- Part.1.E.6 数据容器

- Part.1.E.7 文件

- Part.1.F 如何从容应对含有过多 “过早引用” 的知识?

- Part.1.G 官方教程:The Python Tutorial

- Part.2.A 笨拙与耐心

- Part.2.B 刻意练习

- Part.2.C 为什么从函数开始?

- Part.2.D.1 关于参数(上)

- Part.2.D.2 关于参数(下)

- Part.2.D.3 化名与匿名

- Part.2.D.4 递归函数

- Part.2.D.5 函数的文档

- Part.2.D.6 保存到文件的函数

- Part.2.D.7 测试驱动的开发

- Part.2.D.8 可执行的 Python 文件

- Part.2.E 刻意思考

- Part.3.A 战胜难点

- Part.3.B.1 类 —— 面向对象编程

- Part.3.B.2 类 —— Python 的实现

- Part.3.B.3 函数工具

- Part.3.B.4 正则表达式

- Part.3.B.5 BNF 以及 EBNF

- Part.3.C 拆解

- Part.3.D 刚需幻觉

- Part.3.E 全面 —— 自学的境界

- Part.3.F 自学者的社交

- Part.3.G 这是自学者的黄金时代

- Part.3.H 避免注意力漂移

BNF 以及 EBNF

通常情况下,你很少会在入门书籍里读到关于 Backus-Naur Form(BNF,巴科斯-诺尔范式)和 Extended Backus-Naur Form(EBNF)的话题 —— 它们都被普遍认为是 “非专业人士无需了解的话题”,隐含的另外一层含义是 “反正就算给他们讲他们也无论如何看不懂”……

然而,在我眼里,这事非讲不可 —— 这是这本 “书” 的设计目标决定的。

严格意义上来讲,在《自学是门手艺》中,以自学编程为例,我完全没必要自己动手耗时费力写那么多东西 —— 如果仅仅是为了让读者 “入门” 的话。编程入门书籍,或者 Python 编程入门书籍,都已经太多太多了,其中质量过硬的书籍也多得去了 —— 并且,如果你没有英文阅读障碍,那你就会发现网上有太多非常优质的免费教程…… 真的轮不到李笑来同学再写一次。

我写这本书的目标是:

让读者从认知自学能力开始,通过自学编程作为第一个实践,逐步完整掌握自学能力,进而在随后漫长的人生中,需要什么就去学什么,

…… 不用非得找人教、找人带 —— 只有这样,前途这两个字才会变得实在。

于是,我最希望能做到的是,从这里了解了自学方法论,也了解了编程以及 Python 编程的基础概念之后,《自学是门手艺》的读者能够自顾自地踏上征程,一路走下去 —— 至于走到哪里,能走到哪里,不是我一个作者一厢情愿能够决定的,是吧?

当然,会自学的人运气一定不会差。

于是,这本 “书” 的核心目标之一,换个说法就是:

我希望读者在读完《自学是门手艺》之后,有能力独立地去全面研读官方文档 —— 甚至是各种编程语言、各种软件的相关的文档(包括它们的官方文档)。

自学编程,很像独自一人冲入了一个丛林,里面什么动物都有…… 而且那个丛林很大很大,虽然丛林里有的地方很美,可若是没有地图和指南针,你就会迷失方向。

其实吧,地图也不是没有 —— 别说 Python 了,无论什么编程语言(包括无论什么软件)都有很翔实的官方文档…… 可是吧,绝大多数人无论买多少书、上多少课,就是不去用官方 “地图”,就不!

—— 其实倒不是说 “第三方地图” 更好,实际的原因很不好意思说出来:

- 这首先吧,觉得官方文档阅读量太大了……(嗯?那地图不是越详细越好吗?)

- 那还有吧…… 也不是没去看过,看不懂……(嗯…… 这对初学者倒是个问题!)

所以,我要认为这本 “书” 的最重要工作是:

为读者解读清楚地图上的 “图例”,从此之后读者在任何需要的时候能够彻底读懂地图。

在阅读官方文档的时候,很多人在 The Python Tutorial 上就已经觉得吃力了…… 如果到了 Standard Libraries 和 Language References 的部分,就基本上完全放弃了,比如,以下这段摘自 string —— Common string operations:

Format Specification Mini-Language ... The general form of a standard format specifier is:

format_spec ::= [[fill]align][sign][#][0][width][grouping_option][.precision][type] fill ::= <any character> align ::= "<" | ">" | "=" | "^" sign ::= "+" | "-" | " " width ::= digit+ grouping_option ::= "_" | "," precision ::= digit+ type ::= "b" | "c" | "d" | "e" | "E" | "f" | "F" | "g" | "G" | "n" | "o" | "s" | "x" | "X" | "%"...

读到这,看着一大堆的 ::= [] | 当场傻眼了……

这是 BNF 描述,还是 Python 自己定制的 EBNF…… 为了理解它们,以后当然最好有空研究一下 “上下文无关文法”(Context-free Grammar),没准未来你一高兴就会去玩一般人不敢玩的各种 Parser,甚至干脆自己写门编程语言啥的…… 不过,完全可以跳过那些复杂的东西的 —— 因为你当前的目标只不过是 “能够读懂那些符号的含义”。

其实吧,真的不难的 —— 它就是语法描述的方法。

比如,什么是符合语法的整数(Integer)呢?符合以下语法描述的是整数(使用 Python 的 EBNF):

integer ::= [sign] digit +

sign ::= "+" | "-"

digit ::= "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9"以上的描述中,基本符号没几个,它们各自的含义是:

::=表示定义;< >尖括号里的内容表示必选内容;[ ]中是可选项;" "双引号里的内容表示字符;|竖线两边的是可选内容,相当于or;*表示零个或者多个……+表示一个或者多个……

于是:

interger定义是:由 “可选的sign” 和 “一个或者多个digit的集合” 构成 —— 第一行末尾那个+的作用和正则表达式里的+一样;sign的定义是什么呢?要么是+要么是-;digit的定义是什么呢?从"0"到"9"中的任何一个值……

于是,99、+99、-99,都是符合以上语法描述的 integer;但 99+ 和 99- 肯定不符合以上语法描述的 integer。

很简单吧?反正就是在 ::= 左边逐行列出一个语法构成的所有要素,而后在右边逐行逐一定义,直至全部要素定义完毕。

也许那些在此之前已经熟悉 BNF 范式的人会有点惊讶,“你怎么连 ‘终结符’ 和 ‘非终结符’ 这种最基本的概念都跳过了?” —— 是呀,即便不讲那俩概念也能把这事讲清楚到 “能马上开始用” 了的地步…… 这就是我经常说的,“人类有这个神奇的本领,擅长使用自己并不懂的东西……”

Python 对 BNF 的拓展,借鉴了正则表达式<a href='#fn1' name='fn1b'><sup>[1]</sup></a> —— 从最后两个符号的使用(* +)你可以看得出来。顺带说,这也是为什么这本 “书” 里非要讲其他入门书籍里不讲的正则表达式的原因之一。

又由于 Python 的社区文档是二十来年长期积累的,有时标注方法并不一致。比如,在描述 Python Full Grammar specification 的时候,他们用的语法标注符号体系就跟上面描述 String 的语法不一样了,是这样的:

:表示定义;[ ]中是可选项;' '引号里的内容表示字符;|竖线两边的是可选内容,相当于or;*表示零个或者多个……+表示一个或者多个……

—— 用冒号 : 替代了 ::=,用单引号 '' 替代了双引号 "",而尖括号 <> 干脆不用了:

# Grammar for Python

# NOTE WELL: You should also follow all the steps listed at

# https://devguide.python.org/grammar/

# Start symbols for the grammar:

# single_input is a single interactive statement;

# file_input is a module or sequence of commands read from an input file;

# eval_input is the input for the eval() functions.

# NB: compound_stmt in single_input is followed by extra NEWLINE!

single_input: NEWLINE | simple_stmt | compound_stmt NEWLINE

file_input: (NEWLINE | stmt)* ENDMARKER

eval_input: testlist NEWLINE* ENDMARKER

decorator: '@' dotted_name [ '(' [arglist] ')' ] NEWLINE

decorators: decorator+

decorated: decorators (classdef | funcdef | async_funcdef)

async_funcdef: 'async' funcdef

funcdef: 'def' NAME parameters ['->' test] ':' suite

parameters: '(' [typedargslist] ')'

typedargslist: (tfpdef ['=' test] (',' tfpdef ['=' test])* [',' [

'*' [tfpdef] (',' tfpdef ['=' test])* [',' ['**' tfpdef [',']]]

| '**' tfpdef [',']]]

| '*' [tfpdef] (',' tfpdef ['=' test])* [',' ['**' tfpdef [',']]]

| '**' tfpdef [','])

tfpdef: NAME [':' test]

varargslist: (vfpdef ['=' test] (',' vfpdef ['=' test])* [',' [

'*' [vfpdef] (',' vfpdef ['=' test])* [',' ['**' vfpdef [',']]]

| '**' vfpdef [',']]]

| '*' [vfpdef] (',' vfpdef ['=' test])* [',' ['**' vfpdef [',']]]

| '**' vfpdef [',']

)

vfpdef: NAME

stmt: simple_stmt | compound_stmt

simple_stmt: small_stmt (';' small_stmt)* [';'] NEWLINE

small_stmt: (expr_stmt | del_stmt | pass_stmt | flow_stmt |

import_stmt | global_stmt | nonlocal_stmt | assert_stmt)

expr_stmt: testlist_star_expr (annassign | augassign (yield_expr|testlist) |

('=' (yield_expr|testlist_star_expr))*)

annassign: ':' test ['=' test]

testlist_star_expr: (test|star_expr) (',' (test|star_expr))* [',']

augassign: ('+=' | '-=' | '*=' | '@=' | '/=' | '%=' | '&=' | '|=' | '^=' |

'<<=' | '>>=' | '**=' | '//=')

# For normal and annotated assignments, additional restrictions enforced by the interpreter

del_stmt: 'del' exprlist

pass_stmt: 'pass'

flow_stmt: break_stmt | continue_stmt | return_stmt | raise_stmt | yield_stmt

break_stmt: 'break'

continue_stmt: 'continue'

return_stmt: 'return' [testlist]

yield_stmt: yield_expr

raise_stmt: 'raise' [test ['from' test]]

import_stmt: import_name | import_from

import_name: 'import' dotted_as_names

# note below: the ('.' | '...') is necessary because '...' is tokenized as ELLIPSIS

import_from: ('from' (('.' | '...')* dotted_name | ('.' | '...')+)

'import' ('*' | '(' import_as_names ')' | import_as_names))

import_as_name: NAME ['as' NAME]

dotted_as_name: dotted_name ['as' NAME]

import_as_names: import_as_name (',' import_as_name)* [',']

dotted_as_names: dotted_as_name (',' dotted_as_name)*

dotted_name: NAME ('.' NAME)*

global_stmt: 'global' NAME (',' NAME)*

nonlocal_stmt: 'nonlocal' NAME (',' NAME)*

assert_stmt: 'assert' test [',' test]

compound_stmt: if_stmt | while_stmt | for_stmt | try_stmt | with_stmt | funcdef | classdef | decorated | async_stmt

async_stmt: 'async' (funcdef | with_stmt | for_stmt)

if_stmt: 'if' test ':' suite ('elif' test ':' suite)* ['else' ':' suite]

while_stmt: 'while' test ':' suite ['else' ':' suite]

for_stmt: 'for' exprlist 'in' testlist ':' suite ['else' ':' suite]

try_stmt: ('try' ':' suite

((except_clause ':' suite)+

['else' ':' suite]

['finally' ':' suite] |

'finally' ':' suite))

with_stmt: 'with' with_item (',' with_item)* ':' suite

with_item: test ['as' expr]

# NB compile.c makes sure that the default except clause is last

except_clause: 'except' [test ['as' NAME]]

suite: simple_stmt | NEWLINE INDENT stmt+ DEDENT

test: or_test ['if' or_test 'else' test] | lambdef

test_nocond: or_test | lambdef_nocond

lambdef: 'lambda' [varargslist] ':' test

lambdef_nocond: 'lambda' [varargslist] ':' test_nocond

or_test: and_test ('or' and_test)*

and_test: not_test ('and' not_test)*

not_test: 'not' not_test | comparison

comparison: expr (comp_op expr)*

# <> isn't actually a valid comparison operator in Python. It's here for the

# sake of a __future__ import described in PEP 401 (which really works :-)

comp_op: '<'|'>'|'=='|'>='|'<='|'<>'|'!='|'in'|'not' 'in'|'is'|'is' 'not'

star_expr: '*' expr

expr: xor_expr ('|' xor_expr)*

xor_expr: and_expr ('^' and_expr)*

and_expr: shift_expr ('&' shift_expr)*

shift_expr: arith_expr (('<<'|'>>') arith_expr)*

arith_expr: term (('+'|'-') term)*

term: factor (('*'|'@'|'/'|'%'|'//') factor)*

factor: ('+'|'-'|'~') factor | power

power: atom_expr ['**' factor]

atom_expr: ['await'] atom trailer*

atom: ('(' [yield_expr|testlist_comp] ')' |

'[' [testlist_comp] ']' |

'{' [dictorsetmaker] '}' |

NAME | NUMBER | STRING+ | '...' | 'None' | 'True' | 'False')

testlist_comp: (test|star_expr) ( comp_for | (',' (test|star_expr))* [','] )

trailer: '(' [arglist] ')' | '[' subscriptlist ']' | '.' NAME

subscriptlist: subscript (',' subscript)* [',']

subscript: test | [test] ':' [test] [sliceop]

sliceop: ':' [test]

exprlist: (expr|star_expr) (',' (expr|star_expr))* [',']

testlist: test (',' test)* [',']

dictorsetmaker: ( ((test ':' test | '**' expr)

(comp_for | (',' (test ':' test | '**' expr))* [','])) |

((test | star_expr)

(comp_for | (',' (test | star_expr))* [','])) )

classdef: 'class' NAME ['(' [arglist] ')'] ':' suite

arglist: argument (',' argument)* [',']

# The reason that keywords are test nodes instead of NAME is that using NAME

# results in an ambiguity. ast.c makes sure it's a NAME.

# "test '=' test" is really "keyword '=' test", but we have no such token.

# These need to be in a single rule to avoid grammar that is ambiguous

# to our LL(1) parser. Even though 'test' includes '*expr' in star_expr,

# we explicitly match '*' here, too, to give it proper precedence.

# Illegal combinations and orderings are blocked in ast.c:

# multiple (test comp_for) arguments are blocked; keyword unpackings

# that precede iterable unpackings are blocked; etc.

argument: ( test [comp_for] |

test '=' test |

'**' test |

'*' test )

comp_iter: comp_for | comp_if

sync_comp_for: 'for' exprlist 'in' or_test [comp_iter]

comp_for: ['async'] sync_comp_for

comp_if: 'if' test_nocond [comp_iter]

# not used in grammar, but may appear in "node" passed from Parser to Compiler

encoding_decl: NAME

yield_expr: 'yield' [yield_arg]

yield_arg: 'from' test | testlist现在你已经能读懂 BNF 了,那么,可以再读读用 BNF 描述的 Regex 语法<a href='#fn2' name='fn2b'><sup>[2]</sup></a>,就当复习了 —— 很短的:

BNF grammar for Perl-style regular expressions

<RE> ::= <union> | <simple-RE>

<union> ::= <RE> "|" <simple-RE>

<simple-RE> ::= <concatenation> | <basic-RE>

<concatenation> ::= <simple-RE> <basic-RE>

<basic-RE> ::= <star> | <plus> | <elementary-RE>

<star> ::= <elementary-RE> "*"

<plus> ::= <elementary-RE> "+"

<elementary-RE> ::= <group> | <any> | <eos> | <char> | <set>

<group> ::= "(" <RE> ")"

<any> ::= "."

<eos> ::= "$"

<char> ::= any non metacharacter | "\" metacharacter

<set> ::= <positive-set> | <negative-set>

<positive-set> ::= "[" <set-items> "]"

<negative-set> ::= "[^" <set-items> "]"

<set-items> ::= <set-item> | <set-item> <set-items>

<set-item> ::= <range> | <char>

<range> ::= <char> "-" <char>真的没原来以为得那么神秘,是不?<a href='#fn3' name='fn3b'><sup>[3]</sup></a>

都学到这儿了…… 顺带再自学个东西吧。

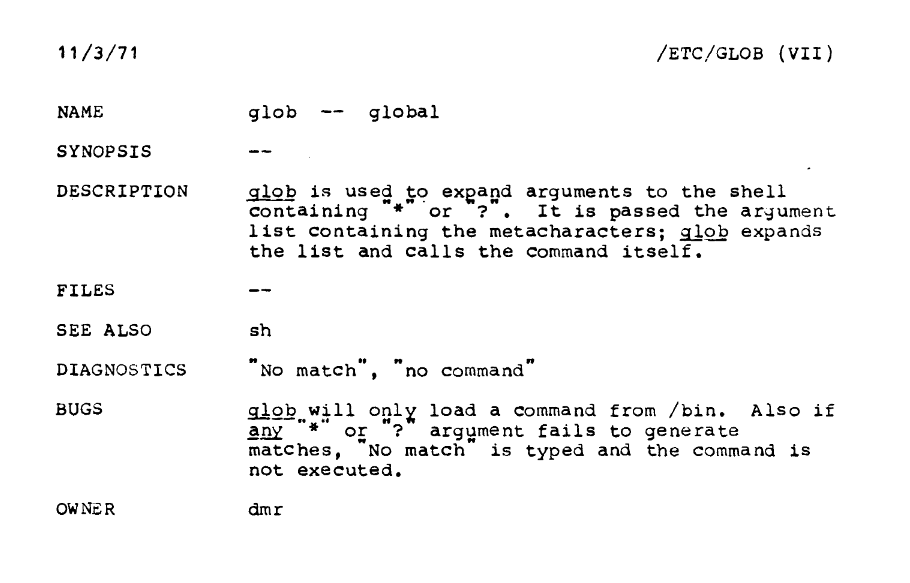

这个东西叫 glob,是 Global 的缩写。你可以把它理解为 “超级简化版正则表达式” —— 它最初是 Unix/Posix 操作系统中用来匹配文件名的 “通配符”。

先看一张 1971 的 Unix 操作系统中关于 glob 的截图:

A screenshot of the original 1971 Unix reference page for glob – note the owner is dmr, short for Dennis Ritchie.

glob 的主要符号只有这么几个:

*?[abc][^abc]

现在的你,打开 Wikipedia 上的关于 glob 和 Wildcard character 的页面,肯定能做到 “无障碍” 理解:

顺带说,现在你再去读关于 Format String 的官方文档,就不会再觉得 “根本看不懂” 了,恰恰相反,你会觉得 “我怎么之前连这个都看不懂呢?”

https://docs.python.org/3/library/string.html#format-string-syntax

在自学这件事上,失败者的死法看起来千变万化,但其实都是一样的…… 只不过是因为怕麻烦或者基础知识不够而不去读最重要的文档。

比如,学英语的时候死活不读语法书。其实英文语法书也没多难啊?再厚,不也是用来 “查” 的吗?不就是多记几个标记就可以读懂的吗?比如,词性标记,v., n., adj., adv., prep.... 不就是相当于地图上的图例吗?那语法书,和现在这里提到的官方文档,不都是 “自学者地图” 吗?

但就是这么一点点简单的东西,挡住了几乎所有人,真是可怕。

脚注

<a name='fn1'>[1]</a>:The Python Language Reference » 1.2 Notation —— 这个链接必须去看一看……

<a href='#fn1b'><small>↑Back to Content↑</small></a>

<a name='fn2'>[2]</a>:Perl Style Regular Expressions in Prolog CMPT 384 Lecture Notes Robert D. Cameron November 29 - December 1, 1999

<a href='#fn2b'><small>↑Back to Content↑</small></a>

<a name='fn3'>[3]</a>:很少有人注意到:在很多编程语言的文法文档中,"$" 被称为 <eos> —— 2017 年 5 月我投资了一个初创公司,听说他们的资产名称叫做 eos…… 我当场就被这个梗逗乐了。

<a href='#fn3b'><small>↑Back to Content↑</small></a>